We can see a little more information by using the parted command. So we have three partitions on the first drive.

The partitions on /dev/sda are listed as /dev/sda1, /dev/sda2, and /dev/sda3. You can scroll through the file to see any other entries that might exist on your computer. We can see the entries for /dev/sda and /dev/sdb. By using the -l (list) option fdisk lists the partition tables on all devices it finds in the “/proc/partitions” file, if it exists. We’re not asking for information on a specific partition. We’ll start with fdisk and pipe it into less. So before doing anything with fsck, we’re going to do a bit of reconnaissance. Before you use fsck you need to ensure you’re going to use it on the correct drive. There’s too much at stake to do otherwise. Pilots don’t jump into an aircraft, start it up, and fly off into the pale blue yonder.

Any command that can make changes to a file system needs to be treated with caution and restricted to those who know what they’re doing. If it finds any problems it can usually fix them for you too.

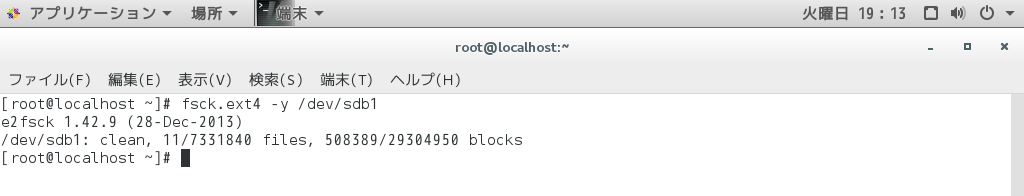

The fsck command lets you check that your file systems are healthy. If their internal tables get scrambled they can lose track of where each file resides on the drive, what size it is, what name it has, and what file permissions are set on them. They’re robust, but they’re not invincible. Modern journaling file systems are better at handling problems that can be caused by a sudden loss of power or a system crash.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)